Jist

A hard problem

May 22nd, 2019

I did it. I solved the mythical 1 kyu on CodeWars. It was truly a journey and I learned so much from this one problem. The problem description went something like this:

Given a positive integer , return the sequence ordered such that each consecutive pair of integers sums to a perfect square. If no such ordering can be found, return false.

Here's the commonly given example, , which also happens to be the smallest for which a solution can be found:

Now, this problem had an easier 5 kyu variant that alone took me a couple days to solve. Maybe I was shooting to high for a solution I could easily adapt to the harder version. Here are the input domains for each difficulty:

n = [2..43] # 5 kyu, easy

n = [2..1000] # 1 kyu, hardYeah, so the hard version is a lot harder. Not to mention after doing a bit of background research on the problem, I've learned it's classified as NP-Hard. Some of the mathy algorithm stuff is over my head but I think it basically means brute force is the only option. There are no "clever" solutions and that's appearently proven by some very abstract math.

But, the cool thing about these problems is that they're prime ground for building up your programming chops. The only way to make your algorithm more efficient is through proper computer science practices: making use of the right data structures, caching recursive calls, memory management, etc.

It's a graph!

One of the first breakthroughs was seeing a graph to be the fundamental structure of the problem. I recognized that each integer would have a set of "partners" from the range that it could be paired with to make a perfect square. For some reason I was visualizing as a table even though I knew it was ultimately about finding a path. Seeing the problem as a graph was a big insight that fueled my problem-solving and research.

I'm slowly trodging through Rosen's Discrete Mathematics, and I had to skip ahead to get a formal definition of what a graph is:

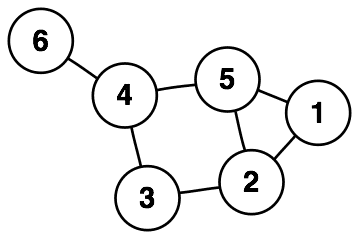

Example,

Note: here we are giving the edges in an undirected way, just to avoid redundancy. Since going from 2 to 5 and 5 to 2 are both valid.

Also: This is a simplified graph, not displaying our desired property of having each edge sum to a perfect square.

And: Some graphs are weighted, I learned about them in my networking classes. The graph in this problem is not. At least in the easy version.

So an undirected, unweighted graph is just a set of vertices (positive integers), and a set of edges (unordered pairs of integers)! At some point I realized this is the simplest way to represent the information in the problem and I would have to find a path that visits all nodes somehow.

It's Hamiltonian!

So by the time I actually found the computerphile video I'd figured out this problem was analogous to the general problem of finding a Hamiltonian Path through a graph. Hamiltonian basically just means "visits every vertex exactly once."

I was relieved to have finally found a formal description of my problem. However, actually implementing it was a challenge. I did find a couple of examples but I wanted to try to implement it myself from the theory alone.

How to model a graph?

The model for a graph that I came up with initially was a simple hash table of the form:

adjTable = {

1: [3, 8, 15],

2: [7, 14],

3: [6, 13],

// ...

}So getting the edges off of any one vertex is just a matter of indexing our table with the vertex. Generating the table can be done with simple range and filter functions.

How to search for a path?

Skimming around some of my books I was able to learn that the two common algorithms for searching a graph are Depth-first and Breadth-first search (DFS and BFS). DFS excels at finding long paths since it explores each branch fully before moving on to the next.

I used JavaScript. Here is what I came up with for a DFS algo, simplifying/commenting as much as possible:

/**

* DFS search for hamiltonian path through graph.

*

* @param {Array} start The initial vertices of the path

* @param {Object} adjTable Hash table representing graph

* @param {Number} n Desired length of path

*/

findPathWithStart = (start, adjTable, n) => {

// hamiltonian terminal case

if (start.length == n) return start

// recursion

for (edge of edges(adjTable, start)) {

// we use ES array destructuring to append edge to start

branch = findPathWithStart([...start, edge], adjTable, n)

if (branch) return branch

}

// no solution terminal case

return false

}is defined as follows:

// return neighbors for last element in start,

// filtering those already used

edges = (adjTable, start) =>

adjTable[last(start)].filter(v => !start.includes(v))

// last - returns last element of list

// includes, filter - built-in JS array methods (self-explanatory)A simple run-through:

start = [1]

adjTable = {

1: [2],

2: [1, 3],

3: [2],

}

n = 3

findPathWithStart(start, adjTable, n) -->

start | returns | edges

----------------------

[1] branch [2]

[1,2] branch [3]

[1,2,3] [1,2,3] --Solution

So basically the solution is calling this function with for every in , until a solution is found, otherwise false. This will check all paths of all starts of the graph for a hamiltonian path, and is our NP-hard certified brute-force solution.

The square sums problem is really just that simple in theory. Implement a DFS over an undirected, unweighted graph in search of a hamiltonian path.

I'm starting to see how this theory stuff can be advantageous :/

The real challenge

The fun part was pushing this algorithm beyond it's initial sluggish maximum calculations of around . Javascript has some nice clean syntax, but there's no hiding the hairyness when going for optimization. The next blog post will be about the harder problem, going up to 1000. Can you guess which one of my ideas panned out and which were a waste of time?

- caching / memoization of recursive calls

- optimizing the adjacency table construction

- optimizing the adjacency table output

- verifying whether a number has already been used more efficiently

- finding the path based on end instead of start

- using different data structures

- sorting the edges, since this would presumably have an effect on DFS search-times

- avoiding newish syntax like destructuring

- praying to the one true god, RNGesus